Zora Neale Hurston

January 7, 1891-January 28, 1960

The Harlem Renaissance writer led many lives: novelist, playwright, anthropologist, maid, manicurist, voodoo apprentice, counterrevolutionary, trailblazer.

I, Charley Morton, time traveler and science geek, have set out to record my interview with author, playwright and anthropologist, and literary luminary of the Harlem Renaissance as part of my "Superheroes of History" project. I am especially excited to talk to her to learn more about how she went about her anthropology work. ‘Coz pursuing a career in forensic anthropology is what I see in my own future.

Liberate the self and all else follows. Never succumb.

Charley Morton: What was life like for you growing up?

Zora Neale Hurston:

I used to take a seat on top of the gate post and watch the world go by. One way to Orlando ran past my house, so the carriages and cars would pass before me. The movement made me glad to see it. Often the white travelers would hail me, but more often I hailed them, and asked, “Don’t you want me to go a piece of the way with you?

They always did. I know now that I must have caused a great deal of amusement among them, but my self-assurance must have carried the point, for I was always invited to come along. I’d ride up the road for perhaps a half mile, then walk back.

Charley Morton: Wow, I would never be allowed to ride off with a stranger! Although, come to think of it, if my parents knew where I have been sneaking off to.... Were your parents okay with that?

Zora Neale Hurston: When they found out about it later, I usually got a whipping. My grandmother worried about my forward ways a great deal. She had known slavery and to her, my brazenness was unthinkable.

Charley Morton: Yeah, I so get that.

Zora Neale Hurston:

Grown people know that they do not always know the why of things, and even if they think they know, they do not know where and how they got the proof. Hence the irritation they show when children keep on demanding to know if a thing is so and how the grown folks got the proof of it. It is so troublesome because it is disturbing to the pigeon-hole way of life.

I was full of curiosity like many other children, and like them. . .. I got few answers from other people, but I kept on asking, because I couldn’t do anything else with my feelings.

Charley Morton: Sounds familiar! Is that how you came to your work—you just kept asking questions?

Zora Neale Hurston: Research is formalized curiosity. It is poking and prying with a purpose.

Charley Morton: How did you get involved in collecting folk stories? Was it something you always wanted to do, or did you just happen into it?

Zora Neale Hurston: At [Howard] University, I got on well both in class work and at the matter of making friends. The teacher who most influenced me was Dr. Lorenzo Dow Turner, head of the English department. Listening to him, I decided that I must be an English teacher and lean over my desk and discourse on the 18th-Century poets, and explain the roots of the modern novel. I made The Stylus, the small literary society on the hill. My joining The Stylus influenced my later moves. So beginning to feel the urge to write, I wanted to be in New York.

Charley Morton: You attended Howard University, an HBCU. Then you were invited and given a full scholarship to finish your undergraduate degree at Barnard College, at the time, a women’s school. How did your relationship with Annie Nathan Meyer, trustee of Barnard College and an anti-suffragist, impact your life?

Zora Neale Hurston: Annie Nathan Meyer offered to get me a scholarship to Barnard, and opened new doors for me. Her generosity set my life on a new path. I dedicated my book, Of Mules and Men, to her: “To my dear friend, Annie Nathan Meyer, who hauled the mud to make me, but loves me just the same.”

Charley Morton: So would you have considered her a mentor? In my world, mentoring young people has become a big deal.

Zora Neale Hurston: (laughs) Well, more like me mentoring her! She and I wrote back-and-forth when I was down in Florida. Turns out, this great society lady who, you’d think, life had given everything to, was looking for writing advice from me!

Charley Morton: Yeah, that’s what struck me about the letters I found—your letters back to Ms. Meyer. It was like you were helping each other, in a way, right?

Zora Neale Hurston: More like I was her “cause” than anything else.

Charley Morton: I’m guessing attending Barnard was highly unusual in the 1920s, especially for a Black woman. What were those experiences like, and how do you think they shaped your interests?

Zora Neale Hurston:

I have no lurid talks to tell of race discrimination at Barnard. I made a few friends in the first few days. Eleanor Beer, who lived on the next chair to me in Economics, was the first. She was a New York girl with a sumptuous home near the Hudson. She invited me down often, and her mother set out to brush me up on good manners. I found out about forks, who entered a room first, sat down first, and who offered to shake hands.

The Social Register crowd at Barnard soon took me up, and I became Barnard’s sacred black cow. If you had not had lunch with me, you had not shot from taw [Charley’s note: this apparently referred to shooting marbles, back in the day].

Charley Morton: Were there courses you took, or any special line of study?

Zora Neale Hurston:

Because my work was top-heavy with English, Political Science, History and Geology, my advisor recommended Fine Arts, Economics and Anthropology for cultural reasons.

I had a term paper called to the attention of Dr. Franz Boas (of Columbia University’s Anthropology department) and thereby gave up my dream of leaning over a desk. He is idolized by everybody who takes his orders. We all called him ‘Papa Franz.” At a party at his house, with a smile, he confirmed, “Of course Zora is my daughter. Certainly!”

I felt that I was highly privileged and determined to make the most of it.

Charley Morton: Then you went on to get a master’s degree from Columbia University.

Zora Neale Hurston: Two weeks before I graduated from Barnard, Dr. Boas sent for me and told me that he had arranged a fellowship for me. I was to go south and collect Negro folk-lore. His instructions are to go out and find what is there. So knowing all this, I was proud he trusted me.

Charley Morton: Did you suffer any failures? How did that affect you?

Zora Neale Hurston: My first six months [in the field] were disappointing. I found out later that it was not because I had no talents for research, but because I did not have the right approach. I went about it asking, in carefully accented Barnardese, “Pardon me, but do you know any folk tales or folk songs?” the men and women who had whole treasuries of material just seeping through their pores, looked at me and shook their heads. Oh, I got a few little items. But compared with what I got later, not enough to make a flea a waltzing jacket.

Charley Morton: What were some of your greatest insights in pursuit of your work?

Zora Neale Hurston: I have known the joy and pain of friendship. I have served and been served. I have made some good enemies for which I am not a bit sorry. I have loved unselfishly, and I have fondled hatred with the red-hot tongs of Hell. That's living.

Charley Morton: As a woman—and especially a Black woman, do you think it’s easier or harder to pursue the things you’re interested in? How have you managed that? Has there been a cost?

Zora Neale Hurston: Sometimes I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me angry. It merely astonishes me. How can anyone deny themselves the pleasure of my company? It's beyond me.

Charley Morton: Good point. I feel like that’s important for us to remember even now!

Zora Neale Hurston: I can say that I have had friends. Friendship is a mysterious and ocean-bottom thing. Who can know the outer ranges of it? Perhaps no human being has ever explored its limits. [...] you will find that trying to go through life without friendship is like milking a bear to get cream for your morning coffee. It is a whole lot of trouble, and then not worth much after you get it.

Charley Morton: Tell me about how you get into the creative mode—are there exercises or prompts that help you unlock that creativity? How would you define “flow” in that spirit?

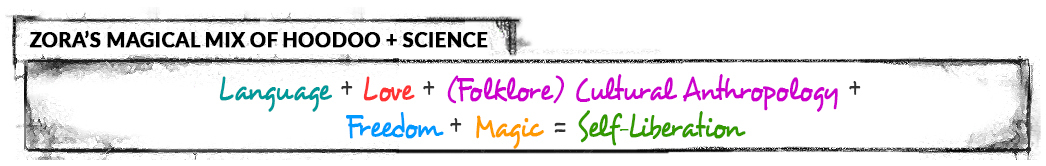

Zora Neale Hurston: I lived with, talked to and studied Negro folk lore in my work—it was more than enough to generate the spirit or “flow”, you’re asking about. In New Orleans, I delved into Hoodoo, or sympathetic magic. I had to go through an initiation. Of my research in the West Indies and Haiti, my greatest thrill was coming face to face with a Zombie and photographing her. This act had never happened before in the history of man. I mean the taking of the picture. What is more, if science ever gets to the bottom of Voodoo in Haiti and Africa, it will be found that some important medical secrets, still unknown to medical science, give it its power, rather than the gestures of ceremony.

Charley Morton: Wow! A Zombie woman? You mean, like, the undead? Talk about spirits!

Zora Neale Hurston:

The ceremonies in Haiti were both beautiful and terrifying. I did not find them any more invalid than any other religion.

It seems to me that organized creeds are collections of words around a wish. I feel no need for such. I know that nothing is destructible; things merely change forms. When the consciousness we know as life ceases, I know that I shall still be part and parcel of the world.

Charley Morton: What was your biggest dream?

Zora Neale Hurston: I saw that Negro music and musicians were getting lost in the betting ring. I just wanted people to know what real Negro music sounded like.

Charley Morton: For teens like me who feel strongly about social injustice and are trying to make an impact (and change the world!), do you have any advice?

Zora Neale Hurston: There are years that ask questions and years that answer.

Want to Learn More?

- Boyd, V. (2004). Wrapped in rainbows: A biography of Zora Neale Hurston. Virago.

- Hurston & Hughes: Two major figures of the Harlem Renaissance The New York Public Library. (n.d.). Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- Hurston, Z. N., & Wall, C. A. (1995). Folklore, memoirs, and other writings. Library of America.

- King, C., Moyer, S., & Scanlan, L. W. (n.d.). What Zora went looking for. The National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved June 19, 2022,

- Pierpont, C. R. (1997, February 10). Zora Neale Hurston, American contrarian. The New Yorker. Retrieved June 19, 2022

- Where to start with Zora Neale Hurston. The New York Public Library. (n.d.). Retrieved June 19, 2022.