John Locke-Unlocked: A Modern Idea of Private Property

How does John Locke’s contribution towards the study of money and private property help us know why we value certain items?

Vladimir Lushasky / CC BY-SA

When I was little, my friends and I had such a huge obsession with My Little Pony toys. I mean, don’t get me wrong. How could you resist not buying the latest edition of the My Little Pony Crystal Princess toy set along with a Rainbow Dash toy! We had it way too good back then.

However, one of my friends in our “herd” (ah! Get it?) always had the nicest and latest edition of the My Little Pony toys, while the rest of us got stuck playing with one pony or the same set of ponies. I always got jealous of her, how she always had the newest ones while I always played with the same one every single time.

Why was it suddenly important, even though I’d never really cared what kind of pony it was as long as I had a toy to play with, even though I knew I could one day get a new set of toys, once I’d earned enough through doing my chores and saving up my allowance?

Turns out, there’s a name for that. It’s known as the “moral foundation of property,” which says that the “value-in-use” of that item increases the need and how much we want it. It became a topic of great philosophical discussion beginning about 300 years ago. And the Enlightenment philosopher John Locke was the guy who set those wheels into motion. (If I really think about it, I wonder if Locke ever imagined his philosophy applying to My Little Pony?!)

Think of it this way: today, children’s toys seem like a basic part of childhood. They are mass-manufactured and marketed.

But back in the day, when such toys might have been crafted individually and by hand, how would one determine how much a product was worth—and who should be paid for creating it?

The value of labor, or things were different way back when

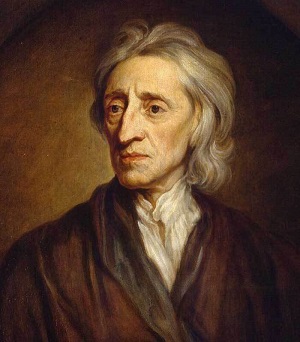

John Locke was originally born in Wrington, England, in the United Kingdom on August 29th, 1632, to Puritan parents. Of course, in America today, we understand the idea of the “Puritan work ethic,” as meaning that if you work hard, you will be rewarded for that effort.

John Locke

In the England of Locke’s time, Puritanism was seen as a strict sect of Protestantism, breaking off from the dominant Church of England. Being Puritan meant following strict rules that forbade certain behaviors such as showing romantic affection in public, speaking against the Bible, breaking the Sabbath, indulging in drink, and even such seemingly innocent pleasures as dancing that were seen as promiscuous, or indulging in personal pride and vanity.

Puritans also resisted central authority. Since, the King of England retained absolute rule, and also served as head of the Church of England, the Puritans were considered rebellious to the Crown.

Locke, perhaps influenced by his Puritan upbringing, challenged the status quo further by asserting that individuals, not the noble landowners or the Crown, had the right to whatever they produced through their labor.

Of course, Locke’s views about property were based on the economy of his day in England, which was primarily centered around land ownership, and creation of value through farming and other land uses. In pre-industrial England, that meant that most landowners were wealthy noblemen, and the people working the land—creating value by farming and bringing produce, milk, wool and meat to market, were tenant farmers without ownership rights themselves. In fact, they had to pay the nobility an annual tax to live on their land; and even then, the owners kept most of the profits. If the crops did poorly, or poor weather conditions meant the cattle or chickens didn’t survive the winter, the tenants would not earn anything—and could not even keep what little of the crops they produced.

In Locke’s view, laborers who work the land and produce the value that comes out of it (think crops, like potatoes and cabbage, or domesticated animals, like sheep and cattle) should be entitled to the value of whatever they produced.

Locke insisted that the price at market for whatever they farmed should go to the worker, not the man who owned the property. Benefiting from one’s own hard work, he argued, is one of the natural rights of man.

Basically, the more work put into making something the more useful it will be seen in the eyes of other people.

It’s encoded in the U.S. Constitution

Between labor and economic value, John Locke emphasized how the usefulness of goods and services demanded and consumed by the individual is inspired by the type of labor that goes into producing them. His foundations of private property, where he posits that the duty of government is to protect the natural rights of people, would subsequently influence Thomas Jefferson to include the right to property, and “the pursuit of happiness” as a natural right in the American Declaration of Independence.

John Locke's Signature

That was then; this is now

What was revolutionary in the eighteenth century is commonplace today: those who produce goods and services should benefit directly from the value of their work.

Our twenty-first century capitalist economy is very different, of course. Most people no longer work the land, but now “create value” by earning a wage through work in manufacturing, farming, service industries, or technology. But they still expect to gain from the fruits of their own labor, and to be able to acquire things to make their own lives, and those of their families, better.

But consumerism has created its own unintended side effect: it has led us to a desire to “keep up with the Joneses”—in essence, to acquire more, bigger, better, newer cars, houses, electronics and even toys, so as not to be seen as falling behind. Wanting the “next big thing” often leads to jealousy and unhappiness, thinking that we might be happy if only we had that one cool thing.

John Locke would undoubtedly be surprised that, today, machines and robots, not people, work the land and the factories. As work evolves, so have our expectations around the value of what is owed to us. And as society evolves, undoubtedly new ideas will grow about how people earn their worth

But Locke’s principles were revolutionary, changing the view of who is entitled to the value of their work from landowner to laborer.

And that, in turn, enabled a new nation, the United States, to repudiate allegiance to a king and declare that “All men are created equal.”

And for that, we can all be grateful.

Want to Learn More?

- Independence Hall Association. "Foundations of American Government" ushistory.org, 30 Nov, -0001. https://www.ushistory.org/gov/2.asp. Accessed on 30 Nov, -0001.

- Karen I. Vaughn. "John Locke and the Labor Theory of Value" Mises Institute, 30 Nov, 1977. https://cdn.mises.org/2_4_3_0.pdf. Accessed on 30 Nov, -0001.

- Graham A.J Rogers. "John Locke" Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc, 20 Jul, 1998. https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Locke. Accessed on 30 Nov, -0001.

- National Archives and Records Administration. "The Declaration of Independence" National Archives and Records Administration, 30 Nov, -0001. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration. Accessed on 30 Nov, -0001.

- L. Edward Allemand. "Two European Influences on the American Revolution: Puritanism and John Locke" DePaul University, 30 Nov, 1975. https://via.library.depaul.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=2677&context=law-review. Accessed on 30 Nov, -0001.