The Great Migration: Finding the Freedom to Make a Living

In the late 19th century, oppressive race laws and economic hardship for Blacks in the South triggered a mass exodus of formerly enslaved people seeking a better life. It wasn’t easy.

Kids are often taught from an early age to learn to confront and combat our problems, rather than run away from them; that to run away from a problem is cowardly, and very rarely results in a solution. But what if, rather than weakening someone, running away actually empowered you? In fact, what if ten thousand people found that, if they fled from their lives to start over, they would find that they now had more freedom and opportunities to create new lives for themselves?

The Great Migration represents just such a flight for greater freedom and opportunity. Between 1916-1970, roughly six million Black Americans left the rural South to move North, West, and Midwest, driven by the desire for new economic opportunities and the chance to escape oppressive segregationist laws. It was not only the concept of escape that drove them to flee their homes, but the prospect of hope as well--hope not only to overcome political and economic challenges, but also to surmount racial prejudice and be viewed as equals in America, regardless of the color of their skin.

Racism is defined as the prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism directed against a person or people on the basis of their membership of a particular racial or ethnic group, typically one that is a minority or marginalized. Symbolic of the racism and discrimination African Americans have faced is through enslavement up to--and through--the Civil War, even beyond President Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation declaring that “all persons held as slaves…should henceforward be free.”

So racism in the South was not new when the Great Migration began in 1916. Although slavery had been abolished in 1865, racism took new forms, particularly in the 1870s after the Civil War, when white supremacy was restored in the South during the Reconstruction Era.

African American family from the rural South arriving in Chicago, 1920. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library (1168439)

Separate and Unequal

During this time, several segregationist policies known as Jim Crow laws were enacted. The name “Jim Crow” itself came from a fictional character in a minstrel show portrayed by a white actor in blackface in the 1830s—reinforcing racial stereotypes and encoding them into state and local laws legally segregating African Americans from white members of society. These laws, most prevalent in the South, continued to be passed and enforced until 1968—a century after Emancipation.

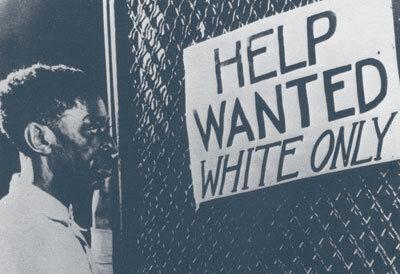

Every southern state and many northern cities had Jim Crow laws that discriminated against black Americans. Sourced: Jim Crow Museum of the Racist Memorabilia

Not only did Jim Crow make it illegal for Black Americans to vote or hold jobs, the laws also authorized forced segregation in public schools and restaurants, as well as on public transportation. There were punishments for not following these laws--perpetrators faced arrest, fines, violence or, in some cases, death. Far from standing up for themselves, Black parents, wanting to keep their families safe--would instruct their children to avoid conflict by acknowledging this was the way it was just “supposed to be.” The effect was to reinforce the inferiority of one’s identity to maintain social control under White authority. A more subtle form of enslavement.

Searching for Economic Freedom

The opportunities African Americans were given were extremely limited, and because of this, many had little choice but to become sharecroppers--renting land from wealthy landowners in exchange for giving the owners a portion of what they grew--to be able to provide for themselves and their families.

Approximately one-third of all sharecroppers between 1877 and the 1940s were Black. Without access to cash, or an independent credit source, this system morphed into a new form of enslavement. High interest rates, unpredictable seasons, and disagreeable landlords caused many of these sharecroppers to find themselves so deeply in debt that it became extremely difficult for them to save a sufficient amount of money to be able to leave the plantations they worked on and explore other opportunities elsewhere.

Sharecroppers picking cotton in Georgia, 1898. photograph by T.W. Ingersoll. Courtesy: Library of Congress

African Americans living in the South were also targeted in public life, mostly by groups such as the Ku Klux Klan (the KKK), a hate group that, although it officially dissolved in 1869, continued to work underground promoting and executing acts of intimidation, many of which included violence and intimidation, such as lynchings and cross burnings.

The time had never seemed better to abandon the lives they had known for decades. In addition to the incentive for economic freedom, natural disasters in the South in 1915 and 1916 put large numbers of Black sharecroppers out of work.

Because of economic uncertainty and long-standing cruelty towards African Americans in the South, the thought of considering leaving behind family and everything one knew to begin the long, expansive trek from the South to the North was not crazy. While the South was composed almost entirely of farms and plantations, in the North there were bustling cities and industrialization--in other words, jobs.

In 1916, a factory wage in the North was three times what a Black man would typically have expected to earn working in the South without natural disasters ruining the crops. Factories and businesses in the North were also in desperate need of cheap labor. In 1914, tens of thousands of Americans had left to fight in World War I; numerous businesses lost thousands of workers. Due to the war, European immigration to the U.S. drastically decreased as well. Some Northern businesses were so desperate for labor they offered to pay the travel fees for African Americans to come North. One such example alone, the Pennsylvania Railroad company, paid the travel expenses of 12,000 Blacks.

Opportunities like these helped many African Americans make the decision to venture out into the world that lay beyond the land their families had worked on for generations--both as enslaved and freed people.

Wayfinding North: at what cost?

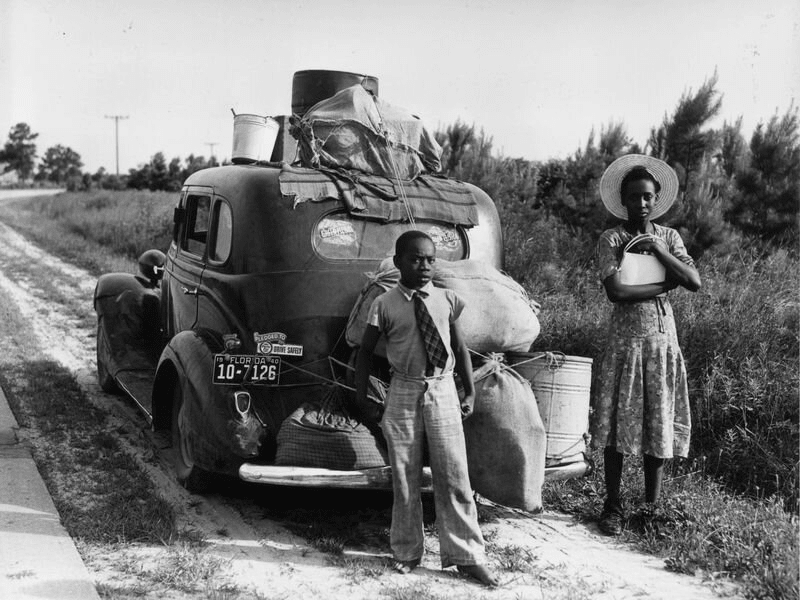

The journey north was by no means an easy one. Mass transit--mainly in the form of buses and trains--was slow and unreliable. Segregation meant that people would have to sit at the back, and could not eat in restaurants or diners, or stay overnight in many towns until they left the Deep South. For many families who lived only off the land, putting together various modes of transportation could be expensive.

Those who set out on the journey depended on a variety of transportation, from trains, buses, and boats, to cars and horse drawn carriages. Public transportation was nearly always segregated, and food and water were never easily accessible. Those did not have enough money to pay for a direct trip would make the journey in stages. They would stop at different places throughout the South along the way to earn more money to continue on their way. It often took a very long time before reaching their final destination. As time went on, it became increasingly expensive to travel--in 1915, a passenger fare was two cents per mile, and in 1918, it was 24 cents a mile.

An African-American family leaves Florida for the North during the Great Depression. Source: Smithsonian magazine

The difficulties Black Southerners faced on their journeys to the North would not be their last. Although from an economic perspective it may seem as if the North was fully prepared to integrate and welcome Black people into urban society with open arms, this was far from the truth. Though there would be more opportunities available to African Americans to live more independently, they would continue to face social discrimination and economic hardship.

Want to Learn More?

“Articles.” The Harlem Renaissance: What Was It, and Why Does It Matter? | Humanities Texas, www.humanitiestexas.org/news/articles/harlem-renaissance-what-was-it-and-why-does-it-matter.

Christensen, Stephanie. “The Great Migration (1915-1960).” Welcome to Blackpast •, 22 Aug. 2019, www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/great-migration-1915-1960/.

“The Great Migration.” AAME, www.inmotionaame.org/print.cfm;jsessionid=f8302900601594050315319?migration=8.

“The Great Migration.” AAME, www.inmotionaame.org/print.cfm?migration=8.

“Great Migration: The African-American Exodus North.” NPR, NPR, 13 Sept. 2010, www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=129827444.

“The Harlem Renaissance.” Ushistory.org, Independence Hall Association, www.ushistory.org/us/46e.asp.

History.com Editors. “Harlem Renaissance.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 29 Oct. 2009, www.history.com/topics/roaring-twenties/harlem-renaissance.

History.com Editors. “Jim Crow Laws.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 28 Feb. 2018, www.history.com/topics/early-20th-century-us/jim-crow-laws.

History.com Editors. “The Great Migration.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 4 Mar. 2010, www.history.com/topics/black-history/great-migration.

“Image.” AAME, www.inmotionaame.org/migrations/topic.cfm?migration=8.

“Moving North, Heading West : African : Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History : Classroom Materials at the Library of Congress : Library of Congress.” The Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/immigration/african7.html.

“Sharecropping.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, www.pbs.org/tpt/slavery-by-another-name/themes/sharecropping/.

Wilkerson, Isabel. “The Long-Lasting Legacy of the Great Migration.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 1 Sept. 2016, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/long-lasting-legacy-great-migration-180960118/.

Women at the Center. “Teaching Women's History: Women of the Great Migration.” Women at the Center, 27 June 2018, womenatthecenter.nyhistory.org/women-of-the-great-migration/.