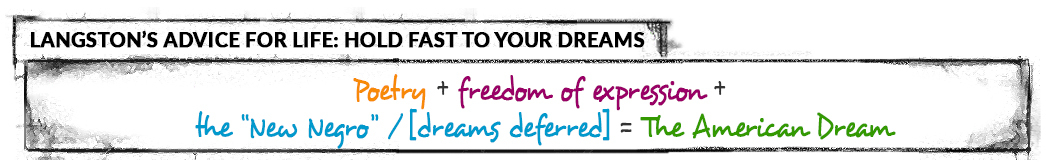

Langston Hughes

A leading light of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes was a poet, author, playwright.

February 1, 1902-May 22, 1967

Langston Hughes is mostly remembered selectively as a “folk” and jazz poet, or author of black vernacular blues and jazz poetry. A leading light of the Harlem Renaissance, he was poet, author, playwright.

I, Charley Morton, time traveler and science geek, have set out to record my interview with “Poet Laureate of the Negro Race” as part of my "Superheroes of History" project.

I swear to the Lord, I still can’t see, why

Democracy means everybody but me.

Charley Morton: Were you inspired to write poetry from a young age?

Langston Hughes:

My grandmother, who raised me almost from birth after my parents divorced, provided me with stories and books—opening me to the power of storytelling. Books were my refuge. After my grandmother’s death, I left Lawrence, Kansas, and went to live with my mother in Lincoln, Illinois, and eventually graduated high school from Central High School in Cleveland, Ohio, where I was awarded class poet and editor of the yearbook.

I went to live in Washington, D.C., with my mother and younger brother, where I worked and wrote poems and short stories. I also attended classes at Howard University. From there, I came to New York, to Harlem and found a home. I attended Columbia University but didn’t like it. I traveled to Africa and Europe as a crewmember aboard the boat SS Malone. I eventually moved back and published my first book, The Weary Blues, in 1926.

Charley Morton: I live just outside Washington, so it’s cool you spent time here. I understand you worked as a bellboy at a hotel in D.C. in the early 1920s while you were going to Howard University. What were you writing about at that time?

Langston Hughes: Yes. I was working as a bellboy at the Wardman Park Hotel in Washington, D.C., in the early 1920s. I was also a student at Howard University. I started to contribute to The Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP, where some of my earliest poems and essays were published. These writings began to establish my reputation as a poet with a unique perspective on the African American experience. The themes of pride, resilience, and the quest for equality that would define much of my later work were already taking shape during those years.

Charley Morton: Were there courses you took at Howard University or mentors who at that time who helped you find your voice as a writer?

Langston Hughes:

Howard University, being a historically black university, provided an environment where African American culture, history, and creativity could be explored. One of my early mentors there was the poet and writer Claude McKay. And Alain Locke, known as the "Dean" or "Father" of the Harlem Renaissance, must have seen something in my writing. He introduced me to the concept of the "New Negro" as a to challenge stereotypes, and promote a more authentic representation of African American life and culture.

My chief literary influences have been Paul Laurence Dunbar, Carl Sandburg, and Walt Whitman. My favorite public figures include Jimmy Durante, Marlene Dietrich, Mary McLeod Bethune, Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt, Marian Anderson, and Henry Armstrong.

Charley Morton: Tell me about your work—especially how you see the evolution of culture giving voice to the Black experience.

Langston Hughes: We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased, we are glad. If they are not, it doesn't matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too.

Charley Morton: That seems like powerful knowledge. Through your writing you broke through cultural barriers and were able to reach beyond the African American community. How did that happen?

Langston Hughes: Perhaps the mission of an artist is to interpret beauty to people—the beauty within themselves. Beauty for some provides escape, who gain a happiness in eyeing the gorgeous buttocks of the ape or Autumn sunsets exquisitely dying.

Charley Morton: Did your experiences as a Black man growing up at the beginning of the 20th century inform your writing? Were there themes from those experiences that informed your writing?

Langston Hughes: [Growing up in Midwest America] I was a victim of a stereotype. There were only two of us Negro kids in the whole class, and our English teacher was always stressing the importance of rhythm in poetry. Well, everybody knows - except us - that all Negroes have rhythms, so they elected me class poet.

Charley Morton: How did that experience shape you?

Langston Hughes: I live in Harlem, New York City. I am unmarried. I like 'Tristan,' goat's milk, short novels, lyric poems, heat, simple folk, boats and bullfights; I dislike 'Aida,' parsnips, long novels, narrative poems, cold, pretentious folk, buses and bridges.

Charley Morton: What about the influence of other expressions of the Harlem Renaissance, like the new music?

Langston Hughes: Jazz, to me, is one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America: the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul—the tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a white world, a world of subway trains, and work, work, work; the tom-tom of joy and laughter, and pain swallowed in a smile.

Charley Morton: What’s your dream?

Langston Hughes: To my mind, it is the duty of the younger Negro artist, if he accepts any duties at all from outsiders, to change through the force of his art that old whispering 'I want to be white,' hidden in the aspirations of his people, to 'Why should I want to be white? I am a Negro - and beautiful!'

Charley Morton: I know racism was meant to keep Black people down, back then. I have read that some of your biggest supporters, and supporters of the Harlem Renaissance were Jewish. What do you think was the affinity there?

Langston Hughes: Very early in life, it seemed to me that there was a relationship between the problems of the Negro people in America and the Jewish people in Russia, and that the Jewish people's problems were worse than ours. The Jewish people and the Negro people both know the meaning of Nordic supremacy. We have both looked into the eyes of terror.

Charley Morton: For teens like me who want to do it all, do you have any advice?

Langston Hughes:

For that, I urge you to listen to my poem, “Dreams”

DREAMS

Hold fast to dreams

For if dreams die

Life is a broken-winged bird

That cannot fly.

Hold fast to dreams

For when dreams go

Life is a barren field

Frozen with snow.

Want to Learn More?

-

Hughes, Langston.

“The Weary Blues by Langston Hughes.” Poetry Foundation, Poetry Foundation,

www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47347/the-weary-blues. Accessed 13 Dec. 2023. -

“Langston Hughes (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior,

www.nps.gov/people/langston-hughes.htm#. Accessed 13 Dec. 2023. -

“Langston Hughes.” DC Writers’ Homes, 26 Nov. 2018,

dcwritershomes.wdchumanities.org/langston-hughes/. -

Lincoln Center Theater. Mule Bone, Lincoln Center Theatre, 1991,

www.lct.org/shows/mule-bone/. - Taylor, Yuval. Zora and Langston: A Story of Friendship and Betrayal. W.W. Norton & Company, 2020.